The main Indiana Jones trilogy is essentially a conversion narrative in which the hero never converts…which is a little strange. Why bother with that narrative if you’re not going to fulfill it? Interestingly, Indy also exists in a universe where all the religions are seemingly true, based on the very real powers each movie’s main artifact displays. This is the final post in my series exploring the weird religious universe that the first three Indiana Jones films create, and this is the film the most closely follows the usual arc of a conversion narrative. If you’d like to read way too much about the history of the Ark of the Covenant, you can do that here, or if you’d rather learn all about the the Hindu sect of Shaivism, you can do that over here. We’re finally to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Just speaking of the film itself, the Holy Grail is an odd choice for an action movie Maguffin, plus the film gives the Grail powers it’s never traditionally had, while smooshing several different folk traditions into one narrative thread. So again, kind of weird. I’ll start this post with an attempt to untangle the Grail lore, and then we can dive into the movie itself.

Let me begin by saying that this is my favorite Indy movie (Although I allow that Raiders is the superior film) possibly because this was the one I saw first. (Full disclosure: I’m friends with multiple people who went into archaeology because of this movie, and I went into religious studies in large part because of the ending of this film. But we’ll get there. Eventually.) I had seen Temple of Doom on TV plenty of times, and was entranced/horrified by the Kali MAAAA scene, but Last Crusade was the first one where I sat down and paid attention. This was strange, obviously, because I didn’t get any of the callbacks to previous films (“Huh. Ark of the Covenant.” “You sure?” “Pretty sure.” “I didn’t know you could fly a plane!” “Fly? Yes. Land? No.”) but also because the film does seem all set to give us the natural ending to a conversion narrative, which is then frustrated in the last moments. But we’ll get there, too.

Grail Lore from Joseph of Arimathea to Dan Brown

Physically, the Grail has been at various times a cup, a chalice, and a platter, and it’s been made from all sorts of different materials, including stone, silver, and gold. It’s sometimes a literal physical object, but it can also appear as a vision. Spiritually speaking, however, if you’re talking about the Holy Grail you could mean one of three (not four, and certainly not five) things.

Thing the First: In the story of the Last Supper, Jesus adapts the traditional Passover Seder by breaking bread and passing it to the Apostles, telling them that it’s his body, and then passing wine around in a cup while saying that it’s his blood. They all share in this bread and wine, and this ended up being the central act of Christian worship, as it evolved first into a literal feast shared by Christian communities, which in turn evolved into the Rite of Communion, which can be a literal transubstantiation into body and blood, (all Catholic and Orthodox churches) or a metaphorical spiritual feast (most Protestant churches). The point of this theological tangent being to tell you: the cup used at the original Last Supper is called The Holy Chalice, but it is also sometimes referred to as the Holy Grail, for instance in Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King.

Thing the Second: There are theories that the crucifixion was not initially a central part of the Jesus story…but I’m not even getting into those right now. As Christianity became increasingly codified, the crucifixion did become a fixed point in Christian canon (and indeed in Western history) and naturally plenty of non-canonical folk stories grew up around the event itself. One was that Joseph of Arimathea caught Jesus’ blood in a cup, which made the cup itself holy, so the Apostles let Joseph take it with him to England for safekeeping.

Thing the Third: Monty Python! Just kidding. In the legends of King Arthur, there is a general belief that the King’s health is intrinsically bound to the health of the land. In some stories, magical, cornucopia-like grails appear to knights, who then have to retrieve them in order to restore the King’s health, thereby saving the land itself. As time went on, these stories were tied into the story of Joseph of Arimathea’s Grail, until they gave us the whole subgenre of grail romances.

Thing the Third, continued: In 12th century France, Chretien de Troyes wrote Perceval, le Conte du Graal, an unfinished piece that tells the story of the naive Perceval, who wants to be a knight. He meets The Fisher King and sees a mystical procession of bloody lances and the grail, but screws up what turns out to be a spiritual test by not asking the King about them. (Much like Gawain and the Green Knight, the moral to this story is super unclear.) The story breaks off before any of the Round Table can get to the Grail. The German writer Wolfram von Eschenbach adapted the story into his epic, Parzival, and finished the narrative. His Parzival is also naive, and also fails the Grail test, but in Wolfram’s version he’s finally able to learn from his mistake and slowly begins a spiritual education to balance his courtly one. The story ends with him becoming the new Grail King. In the following century an anonymous writer tweaked the story in The Quest of the Holy Grail. The Grail appears to the knights as a mystical vision as they sit at The Round Table, and it’s Arthur himself who decides they should pursue it as a religious quest. In this version Perceval is simple and sweet, but ultimately not saintly enough, Lancelot doesn’t stand a chance because of his affair with Guinevere, and Gawain is too hot-headed, so it’s Galahad who reaches the Grail, which is purely religious in this version. In 1485, Sir Thomas Malory used his Le Morte d’Arthur (Dude, spoiler alert, geez….) to retell the Grail story in a slightly different way. Here it’s just another chapter in the adventures of Arthur and his knights, and it is, again, only Galahad who is pure enough to reach the Grail. The Grail itself is a magical cornucopia that gives the knights a feast, and Lancelot’s original interest in going after it is to, and I’m quoting here, get more “metys and drynkes.” Much of the book is concerned with contrasting secular knighthood with Christian knighthood, and the subtle distinction between chivalry and, um, adultery. Malory used the Grail, once again a symbol of purity, to mark out where each of the knights fell on the spectrum of noble to naughty.

Thing the Third-and-a-half: Hands up, who’s read or seen The Da Vinci Code? (It’s OK, there’s no judgment here.) For those few who avoided it, the story combines Grail lore, Mary Magdalene, the first semester of an art history elective, and the theoretical last descendants of Jesus into a thrilling narrative about a globe-trotting academic who gets in no end of scrapes, and who just happens to look exactly like Harrison Ford. The story behind The DVC is very old, and has its roots in a cool piece of religious folk history. Remember how Joseph of Arimathea took the Grail to England? By the Middle Ages, there was also a tradition that Mary Magdalene had travelled to Europe to help spread Christianity, and had retired to a cave in Provence to be a full-time penitent (this is almost exactly my own retirement plan…). There were also lots of clashes throughout Europe between papal authority and local authority, like for instance the Merovingian family, who ruled part of France until being ousted by Pope Zachary in 752. (There were plenty of people who still felt that the Merovingians were the rightful rulers of the land, however.) In the 1800s (probably because Romanticism) writers and artists started sexualizing the Grail, and claiming that the cup was symbolic of female… fertility. So when you stir the Magdalene stories, Merovingian history, and the idea that the grail is really a metaphor for the holy feminine all together, and add the fact that the word san gréal means “Holy Grail” while sang réal means “royal blood,” then sprinkle in tales of the suppression of the Cathars/Knights Templar/Rosicrucians (some of which actually happened), you end up with the heady idea that there is no Grail at all, there is only Mary Magdalene. Well, Mary Magdalene, and the children she supposedly had with Jesus, who are the root of the Merovingian line of kings, who are the rightful rulers of Europe, who are literal descendants of King David, who have been hunted mercilessly by the papacy since the 800s. Makes sense? This theory led to a fantastic 1960s cult/hoax called The Priory of Sion, which in turn led to the book Holy Blood, Holy Grail, which a lot of people thought was non-fiction, and which was cited as fact by Dan Brown, whose prose stylings prove the reality of evil in the universe, if nothing else. Now this all sounds ridiculous, until you consider the fact that Monica Bellucci played the Magdalene in The Passion of the Christ, and she played Persephone, the wife of the Merovingian in The Matrix: Reloaded, so clearly there’s a conspiracy here that probably goes all the way to the top.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade; Or, Grail Lore for Fun and Immortality

OK, now that we all know a bunch of stuff about Grail Lore, we can finally get into the movie! What does all this stuff have to do with Indiana Jones? Well, this is the movie that takes Indy’s story in the strangest direction. First, the film makes it very clear that Indy is a Grail Knight, which means he is possibly destined to find the Grail and protect it from the Nazis. It’s also the completion of the conversion narrative arc that started (in Indy’s chronology) in Temple of Doom. However, Indy once again fails to protect the all-important religious icon, and he never really seems to convert, so both of these arcs are frustrated.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was originally meant to be a wacky horror/action/comedy that sent Indy to a haunted Scottish castle, which is, in my opinion, one of the great lost films of the 80s, because that would have been AMAZING. But since Steven Spielberg had just worked on Poltergeist, he and Lucas decided to try a new direction. How about an opening story about a more Arthurian version of the Grail, still set in Scotland, followed by a hunt for the Fountain of Youth in Africa? This could be fun…. except that it gradually morphed into Indy battling the Monkey King and finding the Peaches of Immortality….while still in Africa, even though the Monkey King is really blatantly Chinese, and his great epic, The Journey to the West, only takes him as far as India, and he’s not really a villain in the story per se, and how exactly were you planning to incorporate the Buddha, and oh, yeah, why is Indy battling a cannibalistic African tribe, at which point I have to set my love of this series aside and ask, did you guys literally look at all the racist elements of Temple of Doom and say, “Surely we can top this” because that’s how it’s starting to seem.

Fortunately wiser heads prevailed, and the script was retooled again.

Spielberg and Lucas kept coming back to the Grail. Lucas had rejected it as “too ethereal” to make a potential icon, and Spielberg was worried that “the Holy Grail remains defined by the Pythons” which, fair enough. Since Spielberg didn’t think the Grail itself was terribly compelling, they amplified it with the power to heal and to grant immortality (kind of) and then tied it into Indy’s relationship with his father. Since Henry Jones, Sr. has spent his life searching for the Grail, Indy gets to see his dad and his own past in a new way by joining the quest. This also made Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade another entry in a weird movie trend of 1989, in which the hero’s Daddy issues are conflated with a quest for some version of God—this also happens in Star Trek V and Field of Dreams.

This is also the most Christian of the Indiana Jones movies—and I mean that in the sense that it’s the only film whose opening gambit and main plot involve relics specifically significant to the Christian community. Where Raiders shifts from a native South American relic to a Judaic one, and Temple goes from a Chinese funerary urn to the Hindu Sankara Stones, Last Crusade goes from a decades-long hunt for a piece of the True Cross to a centuries-long hunt for the Grail.

We begin with one of Indy’s early adventures, the hunt for the Cross of Coronado. As far as I was able to find this cross was invented for the movie, but within the reality of the film it would be considered an important relic, as it contains a piece of the True Cross. This is a trope in much of medieval lore and custom: many churches claimed to have a splinter of the True Cross, or a nail (for instance, there’s one in the Spear of Destiny mentioned above), or a saint’s fingerbone enshrined in their altars. Now there are several things that make this an interesting choice for Last Crusade. First, this cross, with its tiny piece of the more important Cross, serves as an amuse bouche to the main event of the Grail later on. But most interesting for the purposes of this post is Indy’s reaction to the Cross. He doesn’t have any reverence for the Cross as a religious item, let alone as a relic—his desire to save it from the treasure hunters is purely archaeological. He reiterates the idea that “It belongs in a museum” because it was owned by Coronado—not, “It belongs in a church!” because it contains a relic. This secular response becomes even more interesting when we meet Henry Sr., literally hand-drawing a stained glass window and saying “May He who illuminated this, illuminate me”—which is a fairly straightforwardly religious thing to say. So this, coupled with Jones’ snide comment about Sunday School in Raiders, imply that he had a religious upbringing, which he had already rejected, or at least supplanted with his more scientific archaeological interest, by the time he was 13 years old.

When we cut to present-day Indy he’s still just as cavalier about the cross, despite the fact that as soon as the year flashes up, we know that this is a post-Sankara Stones and Ark Indy. This is an Indy who has witnessed two different mystical events from two different religious traditions, thus proving that both of these religions are, for lack of a better word, “real”—and yet his only interest in a relic of the True Cross is historical. This is underscored when Indy emphasizes that archaeology is the search for “facts, not truth” and that scientists “can’t afford to take mythology at face value.” While academically responsible, this is still a heady thing to say to a group of undergrads in the late 1930s, when religious studies departments are only just starting to break away from divinity schools, and people still believe that mummy’s tombs are cursed. It’s also a fascinating thing to hear from one of two living humans who know that the Ark of the Covenant is full of angry face-melting ghosts.

Once Indy meets Walter Donovan, amateur historian and part-time secret Nazi, we take our first real deep dive into the Indy-fication of the Grail story:

As Indy reads the Latin inscription giving the Grail’s location, Donovan claims that the Grail is the cup used by Jesus during the Last Supper, which was then used to catch his blood during the crucifixion, and was entrusted to Joseph of Arimathea who brought it to England. Indy replies by saying, “The Arthur Legend.” Except… what Donovan has done is conflated the Holy Chalice and the Holy Grail, and that has nothing to do with Arthur? Indy recites a legend, original to the film, in which three English brothers went to the Holy Land together, with two of them returning to Europe a century later. One died in Italy, and the other made it all the way back to England, and for some reason told people that he’d seen the Grail. Donovan claims that the Latin inscription belongs to the second brother, and also, by the way, your dad was looking for the knight’s tomb but has since been kidnapped by Nazis probably, and I think this information is supposed to shock us enough that we don’t notice that King Arthur’s existence is a historical fact in Indiana Jones’ universe. Then the movie shuffles us along to the mic drop of the conversation, Donovan saying the line “Find the man and you will find the grail,” which neatly combines the two threads of the film, and allows Indy to have a completely secular quest if he prefers that. Oh, and Donovan also conflates “eternal life” with “eternal youth,” which is the kind of rookie mistake that bites people in the ass when they make deals with the Devil.

Indy goes back to check in with Marcus, asking, “Do you believe, Marcus? Do you believe the grail actually exists?” Which isn’t really the important part. The Grail can exist, there can be a physical cup that was used at the Last Supper and/or crucifixion. But when you drag the concept of “belief” in you’re implying that you think the grail has particular powers. Marcus’ reply is a defanged version of his anger at Indy in Raiders:

The search for the Grail is the search for the divine in all of us. But if you want facts, Indy, I’ve none to give you. At my age, I’m prepared to take a few things on faith.

Now, the interesting thing here is that Marcus’ take is similar to the Arthurian version: searching for the Grail was a test that proved the worthiness of Arthur’s knights, so that could be “the divine in all of us.” But in Christian tradition it’s simply a relic, meant to be venerated. Indy arms himself with Henry’s Grail diary (Henry Jones Sr.’s Grail Diary is the Judy Blume book I always wanted…), gazes at his dad’s weirdly specific Grail Tapestry, and he’s off.

Using the diary as a guide, Indy goes to Europe, meets Dr. Elsa Schneider, and the search for the Grail takes them into the catacombs of a medieval church. Unfortunately, simply by looking for the Tomb of Sir Richard, they’ve run afoul of The Knights Templar. The Rosicrucians. The Brotherhood of the Cruciform Sword! A group of people sworn to protect the hiding place of the Grail. Their way of protecting the Grail is to engage in extremely high profile boat chases! And it’s been effective for over 1000 years. Kazim, the only one left after the boat chase, asks Indy to ask himself why he seeks the Cup of Christ: “Is it for His glory, or for yours?” (Notice that “to keep the Nazis paws off of it” is not an option here.) Indy sidesteps this completely, telling Kazim that he’s looking for his father, and Kazim replies by informing him where Henry Sr. is (HOW DOES KAZIM KNOW??? And why don’t they keep him around, since he also theoretically knows the location of the Grail???) but again, an interesting moment is subsumed in action. Since Indy can keep reiterating that he’s looking for Henry, he can avoid the idea that he’s also on a quest for the Grail, in much the same way that he kept insisting that his hunt for the Ark was for historical purposes only. This keeps him a secular hero surrounded by people who truly believe in the divine properties of the artifacts.

To fast forward a bit: Indy finds Henry, discovers that Elsa’s a Nazi, also discovers that his dad and Elsa hooked up, and father and son both escape to head to the Canyon of the Crescent Moon, AKA Grailsville. Henry is shocked by Indy’s willingness to machine gun the crap outta Nazis, and then we come to a moment that stunned me as a child watching the film.

After they seem to have escaped, Henry insists that they go back for the diary, so they’ll have clues to get through the requisite Grail booby traps.

Indiana: Half the German Army’s on our tail and you want me to go to Berlin? Into the lion’s den?

Henry: Yes! The only thing that matters is the Grail.

Indiana Jones: What about Marcus?

Henry: Marcus would agree with me!

Indiana: Two selfless martyrs; Jesus Christ.

So, here’s the moment that stunned me: Henry slaps Indy for saying this. And Indy, who has just killed a ton of Nazis, flinches away like a, well, like a slapped child. There’s a lot of history embedded in that moment. The scene continues:

Henry: That was for blasphemy! The quest for the Grail is not archaeology; it’s a race against evil! If it is captured by the Nazis, the armies of darkness will march all over the face of the Earth! Do you understand me?

The story, which has so far just seemed like a rollicking adventure, has now been framed as a battle between good and evil, just as the race for the Ark was in Raiders. More importantly, we now know that Indy was raised by a man religious enough to slap another man in the face for breaking the 3rd Commandment (I’ll just quietly mention here that Henry is totes cool with fornicating with Nazis…) yet Indy insists that he’s only in these quests for the historical value now, having matured from his old “fortune and glory” days. Surrounded by true believers, he is choosing moment-by-moment to reject the spiritual dimension of his Grail quest.

They raced back to Berlin, where Elsa claims that she believes in the Grail, not the swastika, and Indy parries that she “stood up to be counted against everything the Grail stands for”—which again is what, exactly? We know what the Nazis stand for, but presumably parsing out exactly what the Grail stands for would involve getting into some uncomfortable theological ground—we know that it grants either youth or immortality, but does its power also prove that a certain type of divinity is real? And does that even matter, in a world where both the Hebrew God and Shiva can incarnate enough to fight their enemies?

Right after he shoots Henry, Donovan explicitly tells Indy, “The healing power of the Grail is the only thing that can save your father now. It’s time to ask yourself what you believe.” But Indy doesn’t tell us what he believes, and he doesn’t turn to any sort of divine or magical intervention. He relies on himself. He uses the Grail Diary—his dad’s lifetime of research, history and lore, to guide him through the tests on the way to the Grail. Naturally, these are not enough. Indy wanted to go over the clues and plan ahead, but Henry was content to find out when he got there, trusting that his intuition—his faith—would get him through the tests. Indy attacks the problem like a scholar, he reads and re-reads the diary, walking into the first test with his nose in his book, mumbling through definitions of the word penitent before he finally makes the connection. This is not an intellectual test: he has to show his humility through the physical experience of kneeling.

The next test, “The Word of God” is the one that I still have to watch through interlaced fingers—not because it’s scary, but because it’s wildly inaccurate.

Indy decides that he needs to spell the Name of God, says “Jehovah” out loud, and steps onto the “J”—just in time for Henry to mumble to himself that Jehovah starts with an “I,” but doesn’t specify which ancient language we’re talking about. Indy almost falls to his death, and berates himself. This is adorable, especially given the Greek drills his dad used to run him through as a kid. There’s just one problem.

(Clears throat as pedantically as possible.) OK, the Grail dates from the 1st Century C.E., right? Because it was present at the Last Supper and/or crucifixion, which took place somewhere between 30-ish and 50-ish C.E. According to the film’s timeline, the Grail was brought to England by Joseph of Arimathea, briefly fell into the hands of Arthur’s Knights, was taken back across Europe, and finally came to rest in the Canyon of the Crescent Moon sometime between the year 1000 C.E.—which was when the Brotherhood of the Cruciform Sword began protecting it, and 1100-ish C.E., when the three Grail Knights moved into the Temple. As we know, two of them returned, one, Sir Richard, dying in Italy, and the other telling his story to a Franciscan Friar in England sometime in the 13th Century. So, presumably it was either a member of the Brotherhood, or one of the Grail Knights themselves who created these tests, which means they did it before the 13th Century, which makes it highly unlikely that any of them would have been calling God Jehovah, because the Brotherhood, who are Aramaic-speaking Semites, would use the term Alaha, and the Knights probably would have just been saying Lord.

There is a plethora of names for God. By a few centuries B.C.E, there were a couple that were most widely used. Since Hebrew doesn’t use vowels, God’s name was written YHWH, and scholars guess that it was pronounced Yah-Weh, which is how that name is written in English now. BUT, at a certain point it became cosmically impolite to say that name aloud, so people began substituting it with Adonai. (This also led to the interesting retrofit where people write “God” as “G-d”, removing the vowel as a sign of respect.) Jehovah, Yehovah, and Iehova is a hybrid word containing the Latinization “JHVH” with the vowels from the name Adonai (a divine word scramble, if you will) and again, while the word did exist by the 13th Century, it was not in wide use. It only became more common in the 16th century, first with William Tyndale’s use of the English “Iehouah” in his translation of the Five Books of Moses in 1530, and then with the all-time world beating Authorized King James Version of the Bible, which used the word “Iehovah” in 1611. However, throughout the 1500s and 1600s, it was just as common to use the word “LORD” in all caps.

So all of this is to say that it’s unlikely that an Aramaic-speaking group building booby traps in about 1000 C.E. would carefully spell out IEHOVAH, complete with a tricksy “J” right there, when that name wasn’t used until 600 years later, in a country none of them ever visited, in a language they didn’t speak. Oh, and also “J” didn’t exist as a letter yet.

Whew.

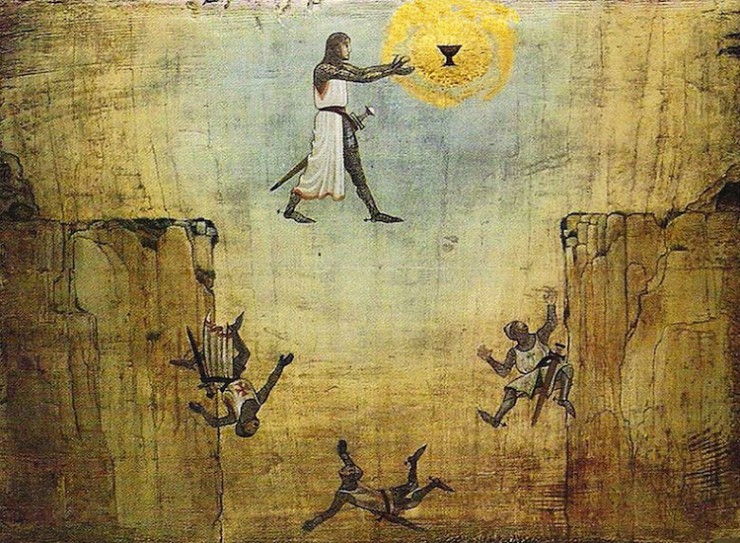

So Indy muddles his way through that test, and makes it to the “Leap from the Lion’s Head” which again thwarts any attempt to attack it intellectually…you kind of just have to do this:

But it also turns out to be a clever engineering trick, as there’s a thin stone bridge perfectly disguised in the grain of the crevasse walls. Here Indy does the thing that’s truly inexplicable to me lo these many years later—why does he scatter sand across it so Elsa and Donovan can follow him? Why doesn’t he leave it uncovered, on the chance that one or both of them will fall into the crevasse, and he’ll be free to save his dad? Why is he actively screwing this up, where during the Ark adventure he had no choice? At least there aren’t any snakes.

He meets the Grail Knight, who not only is alive, but who also tells him that he, too, is a Knight. Poor bastard probably thinks he gets to retire now, but no. We learn that the final test is choosing the correct cup, and that those who choose… poorly will not be happy about it. Where the Ark and Sankara Stones were too holy to be wielded by evil, the grail has its best booby trap built right in, Mirror of Erised-style. Just as Indy’s looking around at the Wall Of Cups, Elsa and Donavan catch up with him. Donovan trusts Elsa with choosing the Grail, and his greed blinds him to the fact that her choice can’t possibly be correct. It also blinds him to the strong implication that Elsa gives him the wrong cup on purpose to murder him, which, again, is an interesting choice to make when you’re being faced with a holy artifact.

Back up at the top I mentioned that this film inspired my interest in studying religion, and it was this scene in particular that did it. See, unlike in the Leap from the Lion’s Head, no faith or intuition was required for Indy to choose wisely; he just had to recognize the cup of a 1st Century C.E. Mediterranean carpenter. The thrill was seeing Indy, after an entire film’s worth of fistfights and machine gun volleys, use his brain to literally outsmart Hitler. (One might even say that his knowledge is his treasure.) He uses his scholarship to find the correct cup, which is simple and made of clay. It might also be his secular nature that allows him to see the correct cup, since a person who worships Jesus might understandably reach for a splendid cup that would reflect their opinions of their Lord.

Now, where Indy’s secular nature trips him up, is that he immediately loses the Grail after he’s used it to heal Henry. Even after he watches it save his father’s life, he holds no reverence for it. And here’s where things get dicey. Indy fails. He fails at being a knight. We see the Grail work—it kept the final Knight alive for all those centuries. The poorly chosen cup killed Donovan, while the wisely chosen cup healed Henry. But when Elsa dies trying to reach it, Henry tells Indy she never really believed in the Grail, as though that has anything to do with her death. Have all the miraculous things happened only to people who believed in them? Well, no. Indy drank from the cup out of desperation, to save his father’s life, and the gambit worked. The cup healed Henry, and is intrinsically the correct cup.

But Indy, even now, fails to see any sort of mystery in this. He asks his dad what he found through the journey, and Henry replies “Illumination”—calling back to the moment when, as a much younger widower with a child to raise, he buried himself in his religious quest rather than facing his grief. Henry has not just gained physical and spiritual healing from the Grail; he has also regained a relationship with his son. So far, so tear-inducing. But when he turns the question back on Indy, we don’t get an answer. Sallah interrupts with a truly idiotic question: “Please, what does it always mean, this… this ‘Junior’?”, even though a father calling a son junior can only mean one thing. This leads to a back and forth about “Indiana” versus “Junior” and the name and identity Indy chose for himself to get out from under the expectations of being “Henry Jones, Jr.” is mocked by the two older men, until Marcus asks if they can just go home already, and rides off haplessly into the sunset. Indy’s own growth, illumination, conversion, rejection of a conversion—it’s all subsumed in a joke. Indy’s interior life remains resolutely interior. Which is good, I think, but it also thwarts the basic conversion arc that the trilogy purposely set up.

If we look at the original Indiana Jones trilogy from Indy’s chronology (Temple, Raiders, Crusade) it follows a clear arc: callow, privileged Western youth has a brush with an “exotic” Eastern religion, and comes to respect another culture. He’s recruited into a larger fight between good and evil, and while his scholarship is helpful, it’s ultimately not as important as faith and intuition. Having been through the experiences with the Sankara Stones and the Ark, being presented with the miraculous healing powers of the Grail should really result in him taking up the mantle of the new Grail Knight, but at the very least he should have a changed perspective on life. Instead, he leaves the Knight standing in the doorway, and he (and the film) duck the question of what the Grail meant to him. He rides off into the sunset seemingly the same inventive, sarcastic hero he’s been all along. I have a theory about that, but to talk about it was have to jump back a few scenes, and jump back in time a few years to a younger me. Child Leah is sitting on the couch, watching Last Crusade.

She’s watching Indy walk into the Grail room, and she’s waiting for the moment when he asks for help. It makes sense, right? Having just gone through the trauma of the walkway, where he clearly thought he was going to fall into a bottomless pit? Having just watched his father get shot right in front of him? He’s going to give up now, and show some vulnerability, because this is the part of the story where the hero throws himself on something larger than himself. But no. He falls back on his intellect. He uses his scholarship to choose the logical cup, and tests his hypothesis on himself. The knight commends him for choosing wisely, and whether Spielberg and Lucas meant this to be a huge moment or not, it certainly was for me. Faced with something so huge – a fight with the Nazis and a dying father – the hero could rely on himself and his own mind. So, for me at least, this was a conversion narrative, because within a few weeks of watching the film I started studying religion (I wanted to know how exactly Indy could identify the right Grail so fast) which led to me taking academic studies in general more seriously (which in turn eventually led to my own epic quest: GRAD SCHOOL). But more importantly, it also led to me relying on my wits to get me through adventures, just like Dr. Jones.

Leah Schnelbach thinks she chose wisely when she decided to write ALL THE WORDS about Indiana Jones. Come talk to her on Twitter!